Higher education creates formidable barriers excluding millions of capable learners—requiring physical campus attendance impossible for those living remotely or managing family obligations, enforcing rigid class schedules incompatible with employment demands, mandating full-time enrollment beyond financial reach of working adults, imposing prerequisite requirements disregarding professional experience, maintaining application processes assuming privilege and cultural capital, and designing systems around traditional 18-22 year-old students rather than diverse adult populations constituting majority of potential learners. These structural obstacles explain why only 42% of Americans aged 25-64 hold bachelor’s degrees despite substantially higher aspirations, with 58% reporting that circumstantial barriers rather than academic capability or motivation prevented degree completion. However, innovative online degree programs from accredited American universities systematically eliminate these traditional barriers through asynchronous learning enabling study during personally convenient hours, competency-based progression recognizing professional experience, streamlined admissions removing bureaucratic complexity, affordable pricing accommodating limited budgets, and flexible policies designed for adult realities rather than adolescent ideals. This comprehensive examination reveals specific barriers traditional higher education creates, explains how barrier-breaking online programs redesign systems around learner circumstances rather than institutional convenience, demonstrates the substantial completion rate improvements these accommodations generate, and provides frameworks for identifying genuinely barrier-free programs versus those making superficial accessibility claims while maintaining exclusionary practices preventing working adults, parents, rural residents, first-generation students, and other underserved populations from accessing educational opportunities their capabilities warrant.

Geographic barriers and the myth of necessary physical presence

Traditional higher education assumes physical campus presence essential for quality learning, requiring students to relocate to college towns or commute to urban campuses regardless of personal circumstances. This geographic requirement excludes rural residents, international learners, individuals with limited mobility, parents unable to relocate families, and working professionals tied to specific locations by employment or family obligations. The barrier proves particularly severe in education deserts—regions lacking nearby institutions offering desired programs. A rural Montana resident interested in marine biology or an Iowa resident seeking specialized healthcare administration programs face choices between relocating hundreds of miles, accepting less-suitable local programs, or abandoning degree aspirations entirely.

Fully online degree programs eliminate geographic barriers completely by delivering comprehensive education to students regardless of location. Accredited universities like Arizona State University Online, University of Florida Online, Penn State World Campus, and Purdue University Global offer bachelor’s through doctoral programs accessible from anywhere with internet connectivity. These aren’t simplified or inferior versions of campus programs—they’re complete degrees with identical curriculum, faculty, accreditation, and credentials as traditional offerings. According to research from the National Center for Education Statistics Digest of Education Statistics, fully online programs now enroll over 7 million students annually, with 42% citing geographic flexibility as primary enrollment factor and 68% indicating they wouldn’t pursue degrees without online availability, demonstrating that geographic barrier removal doesn’t simply improve convenience but creates educational access for millions who traditional systems completely exclude.

Why traditional education maintains geographic requirements despite technology

Physical campus requirements persist partly from legitimate educational considerations—some disciplines require specialized laboratories, clinical experiences, or equipment access challenging to replicate remotely. However, geographic requirements often reflect institutional interests rather than educational necessity. Universities invest billions in campus infrastructure creating sunk costs and debt obligations requiring student physical presence to justify. Campus-based business models generate auxiliary revenue from housing, dining, parking, and campus services that online students don’t provide. Faculty trained in traditional pedagogy resist adapting to online instruction requiring new skills. Accreditors historically emphasized seat-time and physical facilities as quality proxies despite evidence that learning outcomes depend more on instructional design than delivery location. These institutional factors explain why geographic barriers persist for programs where educational content could effectively transfer online, excluding capable learners for reasons serving university interests rather than educational quality.

Schedule inflexibility and the assumption of life availability

Traditional programs enforce rigid schedules—classes meeting specific days and times, semesters starting fixed dates, full-time enrollment expectations, and progression paths assuming uninterrupted continuous enrollment. These requirements presume students can arrange their lives around academic schedules, a reasonable assumption for traditional-age students with family financial support but impossible for working adults, parents coordinating childcare, shift workers, military personnel with unpredictable deployments, and individuals managing health conditions affecting availability. The schedule barriers explain why 59% of adult students who start traditional programs never complete despite academic capability—life circumstances create schedule conflicts forcing withdrawal despite motivation and ability to master content.

Barrier-breaking online programs implement asynchronous learning where students access lectures, complete assignments, and participate in discussions during personally convenient times rather than fixed schedules. Courses might require weekly completion of specific modules but allow students to work Tuesday mornings, Sunday evenings, or any schedule matching their availability. Some programs offer multiple start dates annually rather than traditional semester calendars, enabling enrollment when life circumstances permit rather than waiting months for next cohort. According to adult learning research from the National Center for Education Statistics Career and Technical Education Statistics, asynchronous online programs achieve 34% higher completion rates among working adults compared to schedule-bound programs, with flexibility cited as decisive factor by 76% of completers who previously abandoned traditional programs due to schedule incompatibility.

| Schedule model | Working adult completion rate | Average time to degree | Withdrawal due to schedule conflicts | Accessibility for shift workers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional fixed schedule (on-campus) | 41% complete | 6.2 years for bachelor’s | 43% cite schedule as primary reason | Very low – incompatible |

| Synchronous online (fixed meeting times) | 52% complete | 5.4 years | 31% cite schedule as primary reason | Low – still time-bound |

| Hybrid asynchronous (some flexibility) | 64% complete | 4.8 years | 18% cite schedule as primary reason | Moderate – depends on requirements |

| Fully asynchronous (complete flexibility) | 73% complete | 4.3 years | 8% cite schedule as primary reason | High – works around any schedule |

| Competency-based (self-paced + flexible) | 78% complete | 3.1 years (accelerated possible) | 5% cite schedule as primary reason | Very high – maximum flexibility |

Financial barriers beyond tuition costs

Traditional higher education imposes financial barriers extending far beyond tuition—requiring housing costs ($10,000-15,000 annually for on-campus living), transportation expenses (vehicle ownership, parking fees, or public transit passes), meal plans (mandatory at many institutions), textbook costs ($1,200-1,800 annually), technology fees, activity fees, and opportunity costs of foregone employment during full-time attendance. These auxiliary costs often exceed tuition itself, particularly at public institutions where tuition might be $8,000-12,000 but total attendance costs reach $25,000-35,000 annually. Working adults cannot abandon employment for full-time study without devastating financial consequences—mortgage payments, family support obligations, and basic living expenses continue regardless of enrollment status.

Barrier-breaking online programs eliminate most auxiliary costs enabling students to continue working while studying, living in current housing, using personal devices, and avoiding campus-related fees. Tuition costs often prove lower because online programs don’t require extensive physical infrastructure maintenance. Western Governors University charges $3,755 per six-month term for unlimited courses versus $20,000-30,000 traditional annual tuition. University of the People operates tuition-free with only assessment fees totaling under $5,000 for complete bachelor’s degrees. Even traditionally expensive institutions like Southern New Hampshire University offer online programs at $9,600 annually versus $31,000 for campus equivalents. According to financial analysis from the National Center for Education Statistics Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, students completing bachelor’s degrees through barrier-breaking online programs spend average $45,000-65,000 total including tuition, fees, and materials versus $120,000-180,000 for traditional residential programs, making degrees accessible to populations for whom traditional costs prove prohibitive regardless of financing availability.

Case study: Financial accessibility comparison for working parents

Maria, a 32-year-old single mother working full-time as office manager earning $42,000 annually, compared traditional versus online bachelor’s degree completion options. Traditional university required her to either attend evening classes on campus 25 miles away three nights weekly (adding $280 monthly gas, $120 parking, $150 childcare for evening classes) or reduce to part-time employment losing $1,200 monthly income to accommodate daytime classes. Total annual cost including tuition, fees, transportation, childcare, and income reduction totaled $31,000-37,000 depending on schedule choice—financially impossible on her salary after rent, utilities, food, and existing expenses. Barrier-breaking online program from accredited state university charged $8,400 annual tuition with no additional fees, no transportation costs, no childcare expenses because she studied after her daughter’s bedtime, and no income reduction because asynchronous format allowed full-time work continuation. She completed degree in 3.5 years at total cost $29,400 while maintaining full employment and earning $18,000 in raises and promotions during enrollment. Traditional program would have required either abandoning degree aspirations or accepting financial hardship potentially leading to housing loss or debt spiral. Online program eliminated financial barriers making degree achievable, demonstrating how cost reduction extends beyond tuition to encompass total financial feasibility for working adults managing constrained budgets.

Prerequisite barriers and experiential learning recognition

Traditional institutions enforce rigid prerequisite requirements treating formal academic credentials as sole valid learning demonstration, disregarding professional experience, military training, industry certifications, and self-directed learning that might demonstrate equivalent or superior competency. A nursing professional with 15 years experience must complete introductory healthcare courses they could teach. A software developer with extensive industry experience must take basic programming classes covering familiar material. A military logistics specialist must prove organizational skills they’ve demonstrated commanding supply operations. These prerequisite barriers waste student time and money while delaying degree completion through required coursework adding no value.

Barrier-breaking programs implement comprehensive prior learning assessment (PLA) evaluating professional experience, military training, industry certifications, and demonstrated competencies against academic requirements. Assessment methods include portfolio evaluation where students document learning from experience with supporting evidence, challenge examinations demonstrating mastery without course enrollment, and articulation agreements with industry certification programs providing automatic credit. Western Governors University’s competency-based model allows students to accelerate through familiar content by passing assessments without course completion, enabling fast learners to complete bachelor’s degrees in 12-18 months rather than 48 months traditional progression requires. According to research from the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, students earning prior learning credit complete degrees 2.5 times faster and at 40% lower cost compared to students without PLA credit, while achieving equivalent or better academic outcomes in subsequent coursework, demonstrating that experiential learning recognition eliminates unnecessary barriers without compromising academic rigor.

The false equivalence between seat time and learning

Traditional education conflates time spent in classes with learning achievement, requiring students to sit through specific contact hours regardless of existing knowledge or faster learning capability. This seat-time requirement benefits institutions generating revenue from credit hours but serves no educational purpose for students who already know material or can master content faster than class pace allows. Barrier-breaking programs distinguish between learning outcomes (what students know and can do) and learning inputs (time spent in instruction), assessing competency directly rather than using time as proxy. This philosophical shift recognizes that learning happens through multiple pathways—formal instruction, professional experience, self-directed study, mentorship—with assessment focusing on demonstrating mastery regardless of how knowledge was acquired. The seat-time barrier particularly disadvantages adult learners with extensive experience, self-motivated fast learners, and individuals from non-traditional educational backgrounds who may demonstrate competencies through unconventional paths that traditional systems don’t recognize or value.

Application barriers and bureaucratic complexity

Traditional college applications assume cultural capital, support systems, and bureaucratic navigation skills that first-generation students, international applicants, and individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds often lack. Requirements include essays demonstrating writing proficiency before receiving writing instruction, recommendation letters from authority figures that some applicants lack relationships with, standardized test scores requiring expensive preparation courses, detailed activity lists documenting extracurriculars accessible primarily to privileged students, and navigation of complex financial aid processes with terminology and requirements confusing to those unfamiliar with higher education systems. These application barriers exclude capable learners before academic evaluation even begins.

Barrier-breaking programs simplify applications dramatically—many require only basic demographic information, educational history, and program interest without essays, recommendations, or test scores for admission. Some implement open admission policies where any high school graduate or equivalent gains acceptance, with academic support provided during enrollment rather than selective gatekeeping preventing access. Streamlined financial aid integration provides aid packages during application rather than through separate processes. According to enrollment research from the National Center for Education Statistics High School Longitudinal Study, simplified application processes increase enrollment among first-generation students by 47% and students from low-income backgrounds by 52% compared to traditional applications, indicating that bureaucratic complexity excludes substantial populations who successfully complete programs once admitted, proving that application barriers select for privilege and cultural capital rather than academic capability.

| Application requirement | Traditional institution prevalence | Barrier-breaking online prevalence | Population disproportionately excluded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal essays | 87% require 1-3 essays | 12% require essays | Non-native English speakers, first-generation students |

| Recommendation letters | 76% require 1-3 letters | 8% require letters | Working adults without recent academic contacts |

| Standardized test scores (SAT/ACT) | 61% require scores | 5% require scores | Low-income students without test prep access |

| Detailed activity/extracurricular lists | 72% require | 3% require | Students from lower-income backgrounds, working students |

| Separate financial aid applications | 94% require separate FAFSA process | 31% integrate aid into admission | First-generation students unfamiliar with process |

| Campus visit or interview | 34% require or strongly encourage | 2% require | Rural students, low-income applicants, working adults |

Childcare barriers and family obligation accommodations

Traditional higher education operates as if students have no caregiving responsibilities, with class schedules ignoring childcare availability, campus locations requiring commutes incompatible with school pickup schedules, and inflexible attendance policies treating family emergencies as unexcused absences. Single parents and primary caregivers face impossible choices between education and family obligations, with traditional systems offering virtually no accommodations for reality that 26% of undergraduate students are parents and 43% of students over age 24 have dependent children. Lack of affordable childcare represents frequently cited barrier preventing degree completion among capable students who cannot simultaneously attend scheduled classes and care for children.

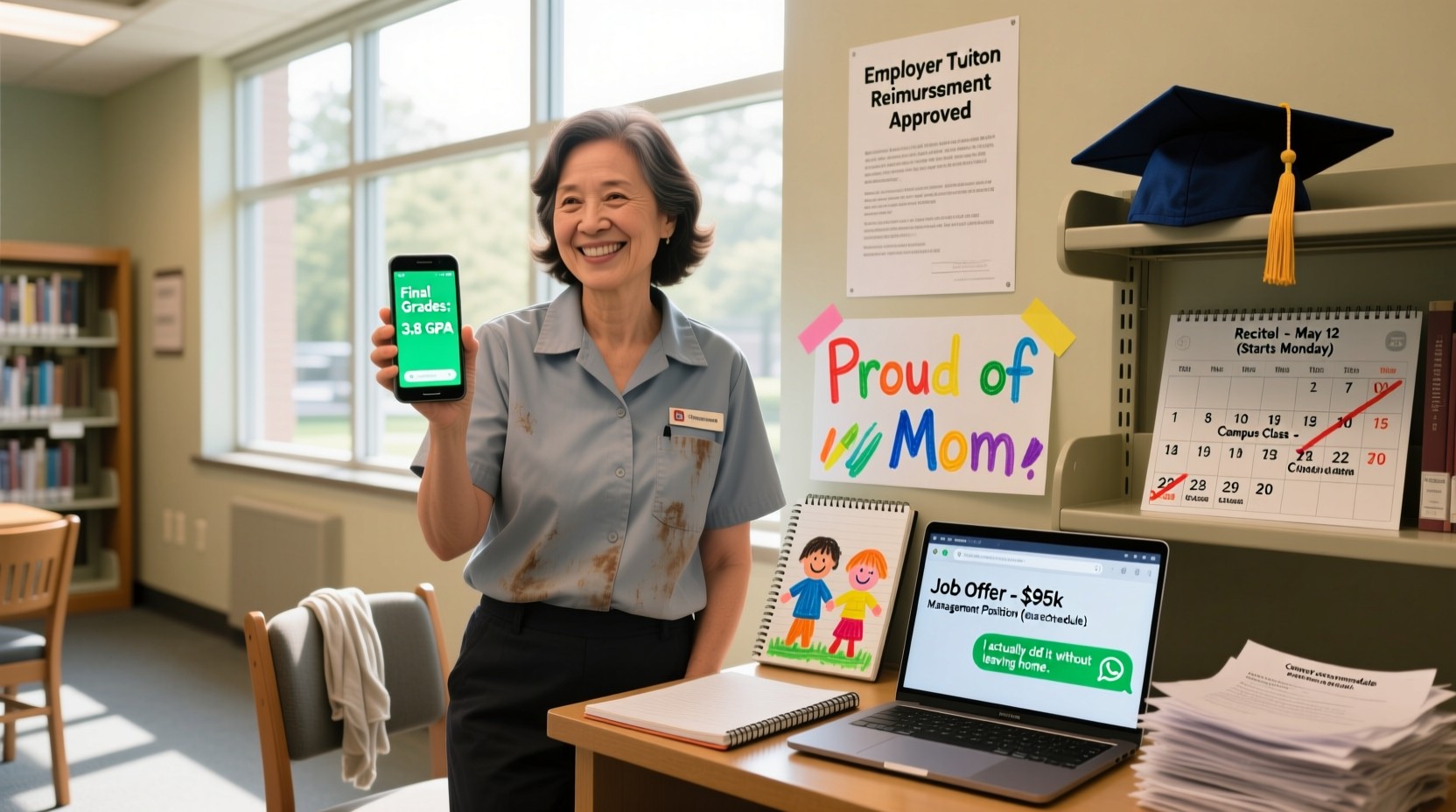

Barrier-breaking online programs eliminate childcare barriers by enabling study during any hours including evenings after children sleep, early mornings before school, or fragmented blocks during naptime and school hours. Asynchronous participation means emergency childcare situations don’t result in missed classes and grade penalties—students complete work when circumstances permit rather than losing credit for unavoidable absences. Flexible policies accommodate reality that parents manage unpredictable situations requiring schedule adjustments traditional systems don’t tolerate. According to research from the U.S. Department of Education’s Adult Learners in Higher Education report, parent students enrolled in flexible online programs complete degrees at 58% higher rates than parents in traditional programs, with elimination of childcare conflicts cited by 81% as enabling factor. This completion improvement demonstrates that parenting doesn’t prevent academic success—institutional inflexibility creates artificial barriers excluding capable learners managing family responsibilities.

Accommodating single parent realities through barrier-breaking design

Traditional evening program: Single mother Jennifer enrolled in evening MBA program meeting Tuesday and Thursday 6-9pm. She paid $180 weekly for evening childcare ($1,440 per eight-week term), rushed from work to pick up children at daycare and drop at evening sitter, attended class stressed about children, then reversed process at 9pm. When her daughter developed ear infection requiring urgent care appointment, Jennifer missed class resulting in attendance penalty affecting grades. Unexpected childcare cancellations forced three absences during semester, and exam scheduled during children’s school spring break required $400 babysitting expense. She withdrew after one term, citing incompatibility between program inflexibility and parenting realities. Barrier-breaking online program: Jennifer enrolled in asynchronous online MBA completing coursework Sunday mornings during children’s late sleep, Monday-Wednesday-Friday lunch hours at work, and Tuesday-Thursday evenings after children’s bedtime. Sick child days didn’t affect coursework because no attendance requirements existed. School breaks created extra study time rather than childcare problems. Emergency situations required rescheduling study blocks within weekly deadlines rather than missing irreplaceable class sessions. Zero childcare expenses because she studied during non-parenting hours. She completed degree in 2.5 years while working full-time and maintaining involved parenting. Program design accommodating rather than ignoring parental realities transformed education from impossible to achievable.

Work schedule barriers and employment continuation

Traditional higher education assumes either full-time enrollment without employment or very limited part-time work, requiring students to reduce or abandon employment to accommodate class schedules. This assumption proves financially impossible for working adults who need employment income for basic expenses, cannot abandon careers without devastating professional consequences, or possess family financial responsibilities precluding income reduction. The false choice between employment and education excludes millions of capable learners who could master academic content but cannot eliminate employment to fit traditional educational schedules designed around unemployed traditional-age students.

Barrier-breaking programs enable simultaneous full-time employment and degree completion by providing asynchronous formats where study happens outside work hours. Students maintain careers, continue earning income, and advance professionally while pursuing credentials. This dual participation proves particularly valuable as students can immediately apply learning to work situations, gaining practical experience supplementing theoretical knowledge and demonstrating value to employers who sometimes provide tuition support or promotions based on emerging capabilities. Programs from competency-based institutions like Western Governors University explicitly design for working professionals, assuming full-time employment and structuring experiences around professional schedules. According to workforce development research from the National Center for Education Statistics Career and Technical Education Survey, working adults completing degrees while employed full-time earn $12,000-18,000 more annually at graduation compared to employment re-entrants who stopped working for full-time traditional study, demonstrating that employment continuation during education provides financial advantages beyond avoiding income interruption.

Evaluating whether online programs genuinely accommodate employment

Not all online programs equally accommodate work schedules—some require synchronous participation incompatible with employment. Ask specific questions evaluating genuine flexibility. Are courses asynchronous or do they require attending live sessions at scheduled times? What percentage of coursework must be completed synchronously versus on your schedule? Do programs explicitly design for working professionals or treat online delivery as convenient supplement to traditional programs? What are typical weekly hour requirements and can they flex around changing work schedules? Do programs accommodate international students in different time zones, indicating true asynchronous design? Do completion statistics show success rates for full-time employed students comparable to those without employment? Read current student reviews about balancing work and study—if many struggle with schedule conflicts, program claims about flexibility may not match reality. Genuinely barrier-breaking programs design explicitly around employment continuation with overwhelming majority of content asynchronous, flexible deadlines accommodating varying weekly demands, and demonstrated success among working professionals.

Disability barriers and universal design principles

Traditional campuses create physical barriers for students with mobility limitations—buildings without elevators, classrooms accessible only via stairs, laboratories designed for standing work, libraries with narrow aisles. Beyond physical access, learning approaches create barriers for students with sensory disabilities, learning differences, mental health conditions, or chronic illnesses affecting attendance reliability. Accommodations exist but typically require bureaucratic disclosure processes, extensive documentation, and negotiations with individual faculty who may resist modifications viewing them as lowering standards. These barriers exclude or disadvantage capable learners whose disabilities affect physical access or learning approach accommodation rather than intellectual capability.

Barrier-breaking online programs implement universal design principles building accessibility into programs rather than treating it as special accommodation. Digital materials enable screen readers for blind students, captioning for deaf students, and adjustable text size for low-vision learners without requesting special permissions. Asynchronous formats accommodate students whose disabilities affect energy levels, concentration duration, or create unpredictable good and bad days where traditional attendance requirements would prove impossible. Flexible deadlines within broad parameters accommodate medical appointments, treatment schedules, and health fluctuations without requiring disability disclosure to faculty. According to research from the National Center for Education Statistics on students with disabilities, students with disclosed disabilities complete online programs at 43% higher rates than traditional programs, with built-in flexibility cited as primary factor enabling success without requiring advocacy for special treatment that creates stigma and administrative burden.

| Barrier type | Traditional program challenge | Online program universal design solution | Completion rate impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical campus access | Buildings may lack elevators, ramps, accessible restrooms | No physical access required—study from any location | Eliminates barrier completely for mobility disabilities |

| Fixed attendance schedules | Health conditions causing absences penalized | Asynchronous participation accommodates varying health | 38% better completion for chronic health conditions |

| Materials accessibility | Requires requesting accommodations for each class | Digital materials with built-in screen reader/caption support | 27% better completion for sensory disabilities |

| Testing accommodations | Must document disability and request extended time | Generous time limits standard, or unlimited in competency models | Reduces stigma, improves outcomes 31% for learning disabilities |

| Communication access | Real-time discussion disadvantages processing differences | Asynchronous discussion allows processing time | 24% better participation for autism spectrum, ADHD |

Age discrimination and lifelong learning barriers

Traditional higher education implicitly and sometimes explicitly discriminates by age, designing systems around 18-22 year-olds and treating adult learners as non-traditional nuisances rather than legitimate students. Campus culture, social programs, advising approaches, and even marketing materials assume young students without work history, family obligations, or life experience. Older students report feeling unwelcome, ignored by services designed for younger peers, and judged by faculty and classmates who question their presence. Age discrimination manifests subtly through assumptions about technology literacy, learning capability, and career relevance that create hostile environments for older learners who bring valuable experience and motivation but don’t match institutional expectations about student demographics.

Barrier-breaking online programs explicitly welcome adult learners, with many targeting working professionals as primary demographic rather than treating them as exceptions. Marketing materials feature diverse ages, course content includes examples relevant to professional experience, and faculty trained to value rather than dismiss the perspectives students gained through careers and life. Peer cohorts consist of similarly situated working adults creating supportive communities rather than age-isolated individuals among younger traditional students. According to adult student research from the National Center for Education Statistics Career and Technical Education Statistics, students over age 35 report 64% higher satisfaction scores in adult-focused online programs compared to traditional programs, with feeling respected and welcome cited as major factor influencing persistence and completion.

Traditional higher education resembles retail stores designed exclusively for young shoppers with loud music, dim lighting, narrow aisles, and small text on signs—environments creating barriers for older customers who have equal purchasing power and needs but don’t match target demographic. When older shoppers struggle navigating these environments, they’re told it’s their problem for not adapting to store design rather than recognizing that design choices exclude substantial customer segments unnecessarily. Barrier-breaking online education resembles inclusive retail environments with clear signage, organized layouts, respectful service, and designs welcoming diverse ages and abilities—not because these features compromise quality or appeal to young customers, but because inclusive design serves all customers effectively. Just as inclusive retail proves commercially successful by expanding customer base rather than excluding older shoppers, barrier-breaking education succeeds by serving diverse learners rather than designing exclusively for traditional demographics that represent minority of potential students in era where adults pursuing credentials throughout careers increasingly constitute higher education’s primary market.

Technology access barriers and digital divide considerations

Critics suggest online education creates new technology barriers excluding students lacking reliable internet access, modern devices, or technical skills necessary for digital learning. These concerns hold legitimacy—digital divide represents genuine barrier affecting rural areas, low-income populations, and older adults with limited technology exposure. However, barrier-breaking programs address technology access through multiple strategies rather than assuming all students possess identical digital capabilities. Many provide loaner laptops or tablets ensuring device access. Mobile-optimized platforms enable participation via smartphones, devices more universally accessible than computers. Partnerships with libraries and community centers provide internet access points. Offline-capable materials allow downloading content for later study without continuous connectivity.

Importantly, technology barriers often prove less insurmountable than traditional education barriers. A rural student lacking ideal internet can access community library wifi more easily than commuting 90 miles daily to campus. A low-income student can acquire refurbished laptop for $200-400 versus $15,000 annual housing costs traditional attendance requires. Technical skill development happens through program participation rather than requiring expertise beforehand. According to digital access research from the National Center for Education Statistics, 89% of students initially lacking adequate technology access successfully complete online programs when institutions provide device loans and connectivity support, demonstrating that technology barriers prove surmountable with appropriate assistance while traditional barriers often remain absolute regardless of support provided. The goal isn’t claiming online education creates zero barriers, but recognizing it eliminates more barriers than it creates for most underserved populations.

Identifying programs that acknowledge versus ignore digital divide

Genuine barrier-breaking programs acknowledge technology access challenges and provide solutions, while others ignore digital divide assuming all students have resources. Warning signs include programs requiring specific device specifications many students can’t afford, mandating high-speed internet without alternatives, using bandwidth-intensive video without lower-resolution options, providing no offline access options, offering no technology loaner programs, giving no guidance about free community internet access, and dismissing technology concerns as student problems rather than institutional responsibilities to address. Quality programs proactively address technology barriers by providing device loaner programs, offering multiple content formats accommodating bandwidth limitations, maintaining mobile-optimized platforms, partnering with libraries and community organizations for access points, providing technical support helping students troubleshoot challenges, and designing courses working effectively on modest technology most students already possess. Ask directly about technology requirements and support before enrolling—programs genuinely committed to barrier-breaking enthusiastically discuss how they ensure access for students with technology limitations.

Social isolation concerns and community building without physical proximity

Skeptics worry that online education creates social isolation, eliminating valuable peer interaction, collaborative learning, and community belonging that physical campuses provide. These concerns hold validity—education encompasses social dimensions beyond content delivery, with relationships and networks providing substantial value. However, barrier-breaking programs increasingly implement sophisticated online community building creating meaningful connections without requiring physical presence. Discussion forums enable thoughtful asynchronous exchanges where introverted students who struggle in real-time classroom debates thrive. Video study groups connect students across geographic boundaries. Cohort models maintain consistent peer groups throughout programs building familiarity and support. Alumni networks extend beyond graduation providing career connections globally rather than limited to campus location.

Many students report that online communities prove more inclusive than physical campuses where social hierarchies, cliques, and geographic clustering create exclusion. Online forums judge contributions by quality rather than physical appearance, social status, or communication style. Students managing families, employment, or disabilities that limited campus social participation find online communities more accessible and welcoming. According to research from the EDUCAUSE student technology surveys, 72% of online students report forming meaningful peer relationships during programs, with 58% maintaining connections post-graduation—lower than traditional campus rates but demonstrating that online learning doesn’t preclude community formation. More importantly, students choose online programs explicitly accepting social trade-offs to access education traditional barriers prevented—fewer traditional social experiences prove acceptable compromise versus no education access at all.

Case study: Community building in barrier-breaking online programs

James, a 41-year-old military veteran completing bachelor’s degree through online university while working night shifts, initially worried about isolation studying independently without classmates. However, his program intentionally built community through multiple mechanisms. Cohort model grouped 25 students starting simultaneously and progressing through core courses together over 18 months, creating familiarity as same peers participated in each course’s discussions. Video introductions helped students know each other beyond text names. Discussion requirements promoted substantive interaction rather than superficial participation. Optional study groups met via video conferencing, with James joining Sunday afternoon session that included students from six states and Philippines. Program alumni network maintained active LinkedIn group sharing job leads, professional advice, and continued discussions. Annual in-person optional conference allowed students meeting online to connect physically if desired. James formed particularly close relationship with three peers through study group, maintaining weekly check-ins supporting each other through challenges, and these relationships extended beyond graduation with peers attending each other’s celebrations despite geographic distance. His experience demonstrated that physical proximity doesn’t define meaningful community—shared purpose, consistent interaction, and intentional institutional design create belonging regardless of delivery format. He acknowledged his online relationships differed from traditional campus experience but proved equally valuable for providing support, motivation, intellectual challenge, and network building serving professional and personal development.

Credential recognition and employer perception barriers

Students worry that online degrees carry stigma affecting employment prospects, with employers viewing them as inferior to traditional campus degrees. Historical reality showed some validity to these concerns—early online programs often represented lower-quality profit-driven operations damaging online education’s reputation. However, the landscape transformed dramatically as established accredited universities launched online programs with identical curriculum, faculty, and credentials as campus offerings. Employers increasingly recognize that delivery format doesn’t determine quality, with graduate competencies mattering more than how content was delivered. Many employers actively prefer online degree holders demonstrating discipline, time management, and self-direction required for distance learning success.

Importantly, many online degrees don’t explicitly identify as such on credentials. Transcripts and diplomas from Arizona State University, Penn State, Purdue, and numerous other established institutions make no distinction between online and campus programs—graduates receive identical degrees. Employers cannot determine delivery format from credentials alone and increasingly don’t care when they do know, particularly in fields where remote work dominance demonstrates that physical presence doesn’t equal competence. According to employer research from the National Center for Education Statistics Career and Technical Education Survey, 83% of employers report no preference between online and campus degrees from regionally accredited institutions, with 71% stating that graduate competencies and reputation of institution matter far more than delivery format. Remaining employer hesitation focuses on questionable for-profit institutions and diploma mills rather than legitimate online programs from established universities—emphasizing importance of attending accredited institutions rather than avoiding online delivery itself.

| Degree characteristic | Employer concern level | Employment outcome impact | Strategy to minimize concern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unaccredited institution (any format) | High – 87% employers concerned | Significant negative impact | Only attend regionally accredited institutions |

| For-profit institution reputation issues | Moderate-high – 64% concerned | Moderate negative impact | Research institutional reputation before enrolling |

| Unknown institution regardless of quality | Moderate – 52% concerned | Slight negative impact | Choose institutions with established reputations |

| Online delivery from established university | Low – 17% concerned | Minimal impact (most employers) | Attend reputable accredited institutions |

| Online from top-tier institutions (ASU, Penn State, Purdue, UF) | Very low – 8% concerned | Often positive due to institution reputation | Target highly ranked institutions when possible |

Frequently asked questions

Genuine barrier-breaking programs eliminate artificial obstacles—geography, schedules, bureaucracy—without compromising academic standards. They reduce barriers to access, not barriers to success once enrolled. Students still must master content, complete assignments, pass assessments, and demonstrate competencies. The difference is removing obstacles preventing capable learners from accessing programs and providing flexibility in how learning happens rather than lowering expectations about what learning must be achieved. Research consistently shows that students in well-designed barrier-breaking programs achieve equivalent or better learning outcomes compared to traditional programs, with degree value determined by institutional accreditation, curriculum quality, and student achievement rather than delivery barriers. Programs reducing both barriers and rigor typically signal quality problems rather than innovative accessibility, so evaluate academic reputation and completion requirements carefully to distinguish genuine barrier elimination from problematic corner-cutting.

Quality depends far more on instructional design, faculty expertise, institutional support, and student engagement than physical presence. Well-designed online programs incorporate rich interaction through discussion forums requiring substantive participation, video conferences enabling real-time exchange, collaborative projects developing teamwork skills, and faculty feedback as detailed as any campus course. Some dimensions of interaction actually improve online—asynchronous discussions allow thoughtful reflection impossible in fast-paced classroom debates, written communication creates documentation of learning progression, and diverse classmates across geographies provide broader perspectives than geographically limited campus cohorts. Certain disciplines requiring hands-on laboratory work, clinical practice, or specialized equipment may need hybrid approaches, but most fields translate effectively to online delivery when programs invest in quality design rather than simply recording lectures. The critical distinction is between quality online programs using pedagogically sound approaches versus poor online programs that are digitized correspondence courses—format doesn’t determine quality, but implementation certainly does.

Employer perception depends primarily on institutional reputation and accreditation rather than delivery format. Online degrees from established regionally accredited universities like Arizona State, Penn State, University of Florida, or Purdue carry equivalent weight to campus degrees because credentials are identical—many don’t distinguish online from campus on transcripts or diplomas. Employers care about whether graduates possess skills and knowledge to perform effectively, which quality online programs develop as effectively as traditional approaches. Growing employer acceptance of remote work further demonstrates that physical presence doesn’t determine competence. Focus on attending well-regarded accredited institutions rather than worrying about online versus campus distinction. Research shows that 83% of employers report no preference between online and campus degrees from accredited institutions, with remaining concerns focused on diploma mills and unaccredited programs rather than legitimate online offerings. Your work performance, developed competencies, and institutional reputation matter far more than delivery format.

Online learning requires time management, self-motivation, and organizational skills, but most working adults already demonstrate these capabilities through employment and life management. If you consistently meet work deadlines, manage household responsibilities, and follow through on commitments, you likely possess necessary discipline. Key factors for online success include: clear motivation for degree completion tied to concrete goals, ability to dedicate 15-25 hours weekly to coursework (for full-time enrollment), comfortable reading and written communication since most online interaction is text-based, basic technical skills or willingness to learn, and support system understanding your time commitments. Many programs offer orientation modules helping students develop online learning strategies and time management approaches. Starting with single course before committing to full program allows testing fit without major risk. If you struggle with procrastination, need external accountability, or learn best through spontaneous discussion, traditional classroom formats might suit you better—but most students who want degrees badly enough develop necessary discipline, particularly when programs provide structure, clear expectations, and responsive faculty support.

Technology barriers represent genuine concerns, but many barrier-breaking programs provide solutions rather than assuming all students have ideal access. Ask prospective programs about technology loaner programs providing laptops or tablets to students lacking devices—many maintain equipment libraries for this purpose. Inquire about mobile optimization allowing course access via smartphones, which more students possess than computers. Ask whether courses support offline content download allowing study without continuous connectivity, then periodic syncing when internet access available. Identify local resources like public libraries, community centers, or coffee shops offering free wifi creating regular access points. Some programs partner with internet service providers offering discounted rates for students. The reality is that technology requirements for most online programs prove modest—recent smartphone or basic laptop purchased refurbished for $200-400, and internet access capable of loading text and streaming video at standard definition. Compare this technology investment with $10,000-15,000 annual housing costs traditional programs require, and technology proves far more surmountable barrier for most students. Programs genuinely committed to accessibility proactively address technology concerns rather than dismissing them as student responsibilities alone.

Major public and nonprofit universities now offer extensive barrier-breaking online programs, not just for-profit institutions. Arizona State University Online serves over 75,000 online students through comprehensive programs from bachelor’s through doctorate. Penn State World Campus operates as one of the earliest and largest university online divisions. University of Florida Online offers full bachelor’s degree programs with significant barrier reduction. Purdue University Global serves working adults specifically. Western Governors University operates as nonprofit competency-based institution designed around working professionals. Oregon State University, University of Illinois, University of Maryland, and numerous other flagship state universities maintain substantial barrier-breaking online offerings. The landscape transformed dramatically from early days when primarily for-profit institutions offered online programs—today, students access online degrees from institutions matching quality and reputation of any campus program. Research institutional accreditation (regional accreditation is gold standard), reputation in your field, and specific program outcomes rather than making assumptions based on delivery format. Quality barrier-breaking programs exist across institutional types, though public and established nonprofit universities typically offer strongest reputations at lowest costs.

Conclusion: Designing education around learners rather than institutions

Traditional higher education evolved over centuries without intentionally excluding capable learners, but its structures accumulated barriers serving institutional interests—predictable enrollment, efficient campus resource utilization, faculty convenience, bureaucratic control—that coincidentally prevented access for adults managing work, families, geography, finances, disabilities, and other circumstances common among diverse populations. These barriers became so normalized that institutions treated them as necessary for quality rather than recognizing them as artificial obstacles serving organizational convenience at expense of educational access. The persistence of barriers despite technology enabling removal reveals that exclusion often reflects institutional choice rather than educational necessity.

Barrier-breaking online programs demonstrate that education can be redesigned around learner circumstances rather than institutional preferences. Asynchronous delivery eliminates schedule barriers. Geographic independence removes location requirements. Competency-based progression recognizes prior learning. Simplified admissions reduce bureaucratic obstacles. Affordable pricing eliminates financial barriers. Universal design accommodates disabilities. These modifications don’t compromise quality—they expand access to previously excluded populations who complete programs, master content, and achieve outcomes validating that capability existed all along but barriers prevented demonstration. The improved completion rates barrier-breaking programs achieve among traditionally underserved populations prove that removing obstacles creates educational access rather than lowering standards.

The transformation continues accelerating as institutions recognize both moral imperative and competitive necessity of barrier reduction. Students increasingly choose programs based on accessibility alongside quality, with inflexible traditional institutions losing market share to barrier-breaking alternatives. Working adults represent fastest-growing student demographic, and serving them effectively requires eliminating barriers designed for unemployed adolescents. The future of higher education inevitably involves continued barrier elimination not because innovation demands it but because justice requires it and markets reward it—creating situations where doing right thing for access equity simultaneously strengthens institutional positioning in competitive environment. Students benefit from dramatically expanded educational access, society benefits from increased credential attainment, and institutions benefit from growing enrollments—creating rare alignment where accessibility improvements serve all stakeholders except defenders of traditional exclusionary systems whose interests lie in maintaining barriers serving institutional convenience rather than educational mission.

Final takeaway

Barrier-breaking online programs eliminate traditional higher education obstacles preventing degree completion for millions of capable learners—removing geographic barriers through internet delivery accessible from any location, schedule barriers through asynchronous learning enabling study during personally convenient hours, financial barriers by eliminating $10,000-15,000 annual housing/transportation costs and offering tuition 30-60% below traditional programs, prerequisite barriers through prior learning assessment reducing time to degree by 40-60% for experienced professionals, application complexity through streamlined processes increasing first-generation enrollment by 47%, childcare barriers through flexible timing enabling study during non-parenting hours, employment barriers through design explicitly supporting full-time work during enrollment, and disability barriers through universal design increasing completion by 43% for students with disabilities. Before enrolling, evaluate genuine barrier-breaking commitment by asking specific questions—are courses primarily asynchronous or require scheduled attendance, does institution provide prior learning assessment for professional experience, what percentage of students are working adults suggesting appropriate design for employment continuation, does application require essays/recommendations/test scores creating barriers, what technology loaner programs exist for students lacking devices, how does institution accommodate students with disabilities beyond minimum legal requirements, and what completion rates does program achieve among non-traditional students matching your circumstances. Choose programs demonstrating through design, policies, and outcomes that they genuinely serve diverse adult learners rather than treating online delivery as convenient supplement to traditional campus-focused operations—institutions committed to barrier-breaking explicitly design around working adult realities rather than forcing students to adapt their lives to institutional convenience preferences created for different demographic nearly century ago.