Online degree marketing advertises “$299 per credit” or “$9,600 annual tuition” creating impressions of affordability, yet students discover actual costs exceed advertised rates by 20-60% through fees cunningly excluded from prominent pricing—$450 per-course online learning fees multiplying across 40 courses, $280 annual technology fees, $320 student services charges, $150 graduation application fees, $85 per-transcript charges, $1,200-2,400 annual textbook costs, $450 proctoring exam fees, and sometimes mandatory laptop purchases or software subscriptions totaling $2,500-8,500 beyond base tuition transforming “$36,000 degree” into $45,000-55,000 actual expenditure. This cost opacity serves institutional interests maximizing revenue while minimizing advertised sticker prices for marketing competitiveness, but creates financial surprises for students who budget based on published tuition discovering hidden costs after enrollment commitment when switching institutions proves difficult and expensive. Moreover, program length variations create dramatic total cost differences—accelerated competency-based programs enable bachelor’s completion in 2-3 years at $15,000-22,500 versus traditional four-year programs costing $40,000-60,000 for identical credentials, while part-time enrollment extending completion to 6-8 years generates $65,000-95,000 total costs through prolonged fee accumulation and delayed career advancement opportunity costs. This comprehensive cost analysis reveals hidden fee structures institutions employ obscuring true prices, demonstrates total cost of ownership calculations incorporating all expenses rather than tuition alone, examines opportunity costs from program length and enrollment intensity, compares net prices after financial aid versus marketing sticker prices, exposes cost manipulation tactics through program structure and billing practices, and provides frameworks enabling prospective students to calculate genuine all-in costs before enrollment preventing financial surprises destroying education budgets and forcing premature withdrawal after substantial sunk costs make completion abandonment financially devastating despite continued enrollment proving unaffordable.

The anatomy of online degree pricing deception

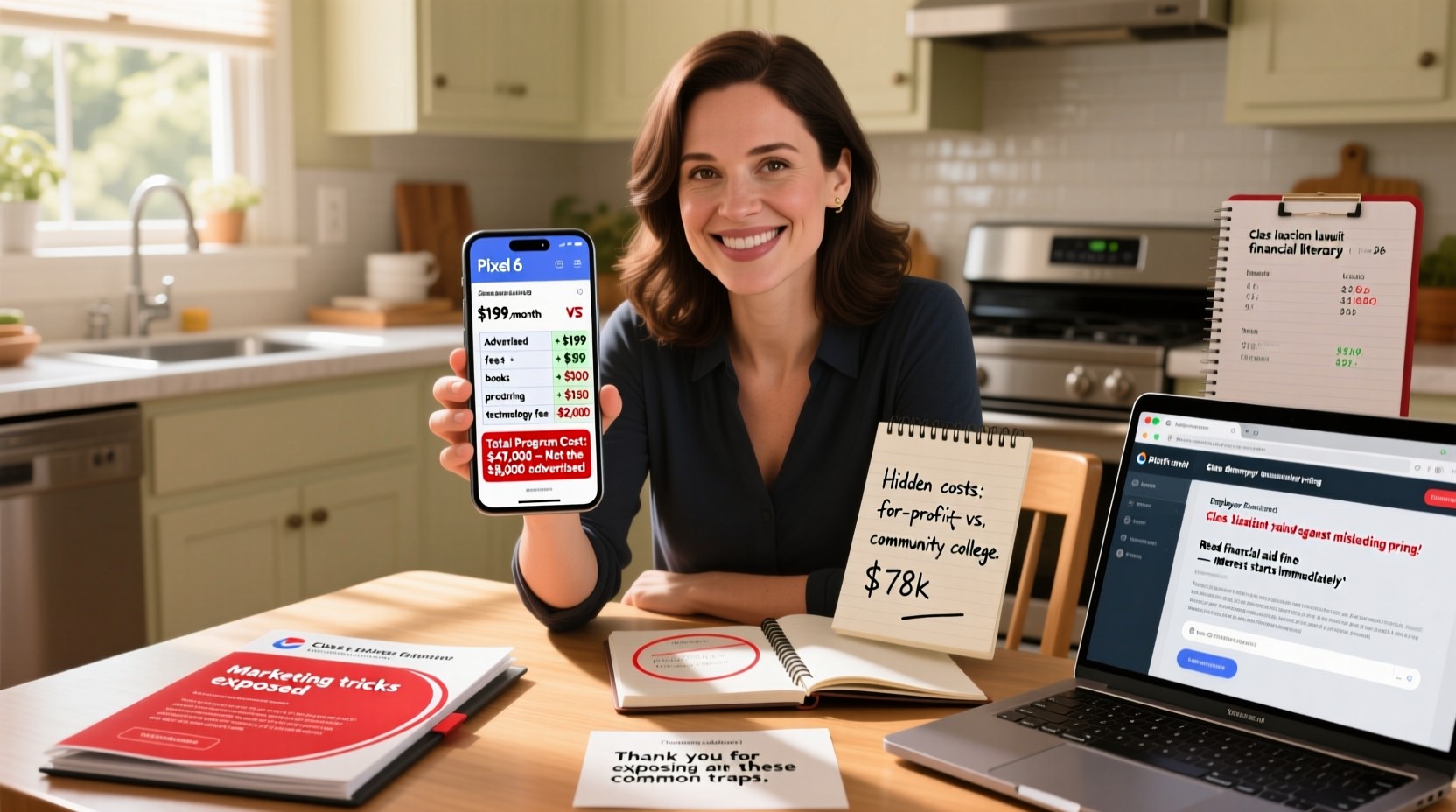

Online program marketing emphasizes per-credit tuition or annual tuition in large prominent text while relegating fees, materials costs, and additional charges to fine print or separate pages requiring multiple clicks to discover. This presentation creates anchoring bias where prospective students fixate on advertised tuition as program cost without recognizing that additional fees substantially increase actual expenditure. A program advertising “$350 per credit” appears affordable at $42,000 for 120-credit bachelor’s degree, but $95 per-credit online learning fee, $450 annual technology fee, $280 student services fee, and $1,800 annual textbook costs increase actual price to $53,980—28% above advertised tuition creating $11,980 surprise expense students didn’t budget for based on marketing materials.

The deception proves particularly problematic because institutions understand cognitive biases affecting consumer decision-making. Prominent low tuition numbers create favorable first impressions influencing program selection, while hidden fees discovered after enrollment commitment exploit sunk cost fallacy where students continue despite higher-than-expected costs rather than abandoning investments already made. According to consumer protection research from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau on college costs, 68% of students report discovering significant fees beyond advertised tuition after enrollment, with 43% stating these hidden costs exceeded $3,000 and 19% exceeding $8,000, demonstrating systematic cost obscuring creating financial surprises affecting majority of students and generating substantial unexpected expenses for many who made enrollment decisions based on incomplete pricing information.

Why institutions obscure total costs through fee structures

Transparent all-inclusive pricing benefits consumers enabling accurate cost comparison and informed decision-making, yet institutions resist transparency because revealing total costs reduces marketing competitiveness. Program advertising “$350 per credit” (appearing cheaper) outcompetes transparent program advertising “$450 all-inclusive per credit” (actual total cost) even when second program proves less expensive overall, because consumers anchor on prominent tuition figures without calculating total expenses. Fee structures also enable incremental price increases—raising tuition 5% generates scrutiny and comparison shopping, while maintaining advertised tuition but increasing various fees by 10-15% accomplishes same revenue increase with less visibility. Online learning fees prove particularly cynical—charging separate fees for online delivery despite online programs having lower infrastructure costs than residential programs represents pure profit extraction rather than cost recovery. Institutions maintain these deceptive practices because transparency would disadvantage them competitively against less transparent competitors, creating race to bottom where honest pricing loses to deceptive marketing unless consumers demand comprehensive cost disclosure before enrollment.

Comprehensive fee cataloging beyond tuition

Online degree costs extend far beyond advertised tuition through multiple fee categories that collectively add 15-45% to base prices. Technology fees ($200-600 annually) supposedly cover learning management systems and infrastructure—despite online students not using physical campus facilities technology fees supposedly support. Online learning fees ($75-150 per course) create perverse situation where programs with lower delivery costs charge premium over traditional instruction. Student services fees ($150-400 annually) fund advising, career services, and support systems though online students often report inferior access compared to campus students paying same fees. Course-specific fees ($50-200 per course) for lab courses, field experiences, or specialized content add unpredictably to costs. Graduation fees ($100-300) charge for diploma production and ceremony access. Transcript fees ($8-25 per transcript) monetize official grade documentation. Late payment fees, drop/add fees, and appeals fees create additional revenue streams.

Beyond institutional fees, students incur substantial costs for required materials and technology. Textbooks and course materials average $1,200-1,800 annually despite aggressive institutional claims about “affordable course materials”—some programs mandate publisher bundled materials preventing used book purchases or rentals. Proctoring fees ($15-45 per exam) for remote examination supervision add $150-450 annually depending on program assessment frequency. Required software subscriptions for specialized programs (statistical packages, design software, programming environments) cost $300-1,200 annually. Laptop or tablet requirements specify expensive equipment ($800-1,500) despite many students owning adequate computers. Internet upgrade costs for bandwidth-intensive video content force some students purchasing faster service adding $20-50 monthly ($240-600 annually). According to comprehensive cost research from the National Center for Education Statistics IPEDS data, median total fees and materials costs beyond tuition average $3,780 annually at public online programs and $4,620 at private online programs, adding $15,120-$18,480 to four-year bachelor’s degree costs—representing 25-35% increase over advertised tuition-only pricing that prospective students rely on for enrollment decisions.

| Fee category | Typical annual cost | Four-year total | Justification claimed | Actual necessity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology fee | $250-550 | $1,000-2,200 | Learning management system, infrastructure | Questionable – online has lower infrastructure costs |

| Online learning fee (per course) | $900-1,800 (10-12 courses) | $3,600-7,200 | Online delivery costs | Unjustified – online costs less than residential |

| Student services fee | $180-380 | $720-1,520 | Advising, career services, support | Reasonable if services actually provided |

| Textbooks and materials | $1,200-1,800 | $4,800-7,200 | Required course materials | Necessary but often inflated through publisher bundling |

| Proctoring fees | $150-450 | $600-1,800 | Exam security and identity verification | Reasonable cost but varies widely by program |

| Software/subscriptions | $200-800 | $800-3,200 | Specialized software for coursework | Varies by program – unnecessary for many fields |

| Graduation/diploma fees | $100-250 (one-time) | $100-250 | Diploma production, ceremony | Minimal cost to institution, revenue generation |

| Total beyond tuition | $2,980-5,830 | $11,920-23,320 | Various justifications | Many fees are profit extraction rather than cost recovery |

Calculating total cost of ownership for degree programs

Accurate cost comparison requires calculating total cost of ownership—combining tuition, all fees, materials, technology requirements, and opportunity costs from program duration. Start with per-credit tuition multiplied by total credits required (typically 120 for bachelor’s, 60 for bachelor’s completion, 30-36 for master’s). Add estimated annual fees multiplied by expected years to completion accounting for full-time versus part-time enrollment pace. Include textbook and materials costs per year. Factor technology purchases or upgrades required. Calculate proctoring fees based on typical exam frequency. Include graduation and transcript fees. This comprehensive calculation reveals genuine program cost rather than deceptive advertised tuition.

Compare total cost of ownership across programs with different structures. Traditional program advertising $380 per credit ($45,600 tuition for 120 credits) plus $4,200 annual fees over four years ($16,800 fees) plus $6,000 textbooks plus $1,200 proctoring equals $69,600 total. Competency-based flat-rate program charging $7,500 per six-month term enabling 2.5-year completion (5 terms, $37,500) plus minimal fees ($1,000) plus included materials equals $38,500 total—44% less despite appearing more expensive per-term than traditional per-credit pricing. The calculation demonstrates that per-credit pricing comparison proves meaningless without considering completion timeline, fee structures, and included versus additional costs. According to cost analysis research from U.S. Government Accountability Office on college costs, students calculating total cost of ownership choose programs averaging $14,800 less expensive over degree completion compared to students comparing advertised tuition only, demonstrating that comprehensive cost analysis enables substantially better financial decisions than reliance on deceptive marketing prices.

The fallacy of per-credit cost comparison

Prospective students instinctively compare per-credit tuition across programs—$320 per credit appears cheaper than $450 per credit. However, this comparison ignores critical factors determining actual total cost. Program requiring 128 credits at $320 per credit ($40,960) costs more than program requiring 120 credits at $380 per credit ($45,600) if first program includes materials and technology ($40,960 total) while second adds $8,000 fees and materials ($53,600 total). Competency-based programs charging $3,755 per six-month term for unlimited credits enable motivated students completing 30-40 credits per term at effective $94-125 per credit versus programs charging $350 per credit limiting students to 12-15 credits per term. Completion timeline dramatically affects total cost—program completed in 2.5 years accumulates fewer years of fees and materials costs than identical per-credit program requiring 4-5 years completion. Focus on total cost of ownership over full degree completion rather than per-credit pricing creating illusion of affordability while actual total costs exceed cheaper alternatives with different pricing structures.

Program length and opportunity cost calculation

Program duration dramatically affects total costs through both direct expenses and opportunity costs from delayed career advancement. Four-year bachelor’s program at $12,000 annually costs $48,000 versus 2.5-year accelerated program at $15,000 annually costing $37,500—accelerated program proves cheaper despite higher annual cost through reduced total duration. Moreover, completing degree 1.5 years faster generates opportunity cost savings through earlier career entry—bachelor’s degree increasing salary from $35,000 to $55,000 means 1.5-year acceleration creates $30,000 additional earnings ($20,000 annual increase × 1.5 years), making accelerated program effectively $7,500 cheaper beyond direct cost savings when incorporating opportunity value.

Part-time enrollment extending program duration increases costs substantially. Student taking 6 credits per semester requires 10 semesters (5 years) completing 120-credit degree versus 8 semesters (4 years) at 15 credits per semester. Five years incurs five years of annual fees versus four, adding $3,000-5,000 in fee accumulation. Five years requires five years of textbook purchases versus four, adding $1,200-1,800. Five years delays career advancement earnings one additional year, costing $15,000-25,000 in foregone salary increases. The extended timeline transforms $45,000 four-year program into $60,000+ five-year program through fee accumulation and opportunity costs. According to completion timeline research from National Center for Education Statistics graduation rate data, students completing bachelor’s degrees in 4 years versus 6 years incur 35% higher total direct costs through extended fee and materials accumulation plus opportunity costs averaging $32,000 from delayed career earnings, demonstrating that program length proves as important as per-year costs in determining affordable degree completion and that accelerated options often provide best value despite higher annual tuition.

| Program structure | Annual cost | Time to completion | Total direct costs | Opportunity cost (delayed earnings) | True total cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated competency-based (WGU-style) | $7,500 + $500 fees | 2.5 years | $20,000 | $0 (baseline) | $20,000 |

| Standard full-time (15 credits/semester) | $11,600 + $3,800 fees/materials | 4 years | $61,600 | $30,000 (1.5 years delayed) | $91,600 |

| Part-time working adult (6 credits/semester) | $4,640 + $3,200 fees/materials | 5 years | $39,200 | $50,000 (2.5 years delayed) | $89,200 |

| Slow part-time (3-6 credits/semester variable) | $2,900 + $3,000 fees/materials | 6.5 years | $38,350 | $80,000 (4 years delayed) | $118,350 |

| Premium traditional online | $18,000 + $4,500 fees/materials | 4 years | $90,000 | $30,000 (1.5 years delayed) | $120,000 |

Net price versus sticker price realities

Published tuition represents sticker price before financial aid, while net price reflects actual student payment after grants and scholarships. These figures diverge substantially—university advertising $15,000 annual tuition might have $9,200 average net price for students receiving typical aid packages. However, net price calculators show averages potentially differing significantly from individual circumstances. Families earning $90,000 annually may receive minimal aid creating net price near sticker price, while $40,000 income families receive substantial aid reducing net price dramatically. Federal Pell Grants provide $7,395 maximum annually (2024-25) for qualifying low-income students, often covering majority of tuition at affordable online programs.

Evaluating net price requires using institutional net price calculators with accurate financial information, recognizing that estimates require verification through actual financial aid applications and award letters. Beware bait-and-switch tactics where freshman year aid proves generous but subsequent years reduce substantially—some institutions use first-year financial aid as recruitment tool then decrease awards when students are committed and transferring proves difficult. Request multi-year financial aid estimates in writing rather than assuming freshman aid continues unchanged. Compare net prices across multiple institutions rather than accepting first offer. According to net price research from National Center for Education Statistics net price comparison data, students comparing net prices across 4+ institutions save average $8,400 over degree completion versus students accepting first admission offer without comparison shopping, demonstrating that financial aid comparison proves as important as tuition comparison in identifying affordable programs and that effort invested in comprehensive cost comparison generates substantial savings justifying time invested.

Case study: Sticker price versus actual cost comparison

Jennifer, a single mother earning $38,000 annually with one dependent, compared three online bachelor’s programs for business management. Program A (state university) advertised $11,200 annual tuition, seemed most affordable. Program B (private nonprofit) advertised $18,600 annual tuition, appeared expensive. Program C (competency-based) charged $7,500 per six-month term ($15,000 annually traditional pace), mid-range price. However, net price calculations revealed different reality. Program A: After $5,900 Pell Grant and $2,000 state grant, net tuition $3,300, plus $3,600 annual fees and materials, actual annual cost $6,900, four-year total $27,600. Program B: After $5,900 Pell Grant and $8,200 institutional grant (generous financial aid), net tuition $4,500, plus $4,200 fees and materials, actual annual cost $8,700, four-year total $34,800. Program C: After $5,900 Pell Grant (covered entire tuition since completion in 2.5 years reduced aid years but accelerated pace offset this), minimal fees $400 annually, books included, actual cost $1,000 over 2.5 years plus 0.5-year without aid coverage at $7,500, total cost $8,500. True cost comparison: Program A (appearing cheapest) actually cost $27,600, Program B (appearing most expensive) cost $34,800, Program C (mid-range advertised) cost only $8,500—69% less than “cheapest” option. Jennifer’s decision based on sticker price would have cost $19,100 more than optimal choice, demonstrating that net price after aid combined with program duration calculations proves essential for accurate cost comparison rather than relying on advertised tuition creating false affordability impressions.

All-inclusive versus itemized pricing strategies

Some institutions adopt all-inclusive pricing incorporating tuition, fees, books, and materials into single comprehensive rate, while others use itemized pricing separating costs into multiple line items. All-inclusive pricing provides transparency enabling accurate budgeting—students know exact total cost without surprise additional charges. Western Governors University includes course materials in tuition creating predictable costs. Some programs provide technology grants or include required software subscriptions. However, all-inclusive programs may have higher sticker prices despite lower total costs compared to programs using itemized pricing with hidden fees that collectively exceed all-inclusive rates.

Evaluating pricing strategies requires calculating total costs under each model. Program charging $450 per credit all-inclusive ($54,000 for 120 credits, everything included) may prove cheaper than program charging $360 per credit ($43,200) plus $120 per-credit online learning fee ($14,400), $250 annual technology fee ($1,000), $1,600 annual books ($6,400), and $400 proctoring ($1,600) totaling $66,600—18% more than “expensive” all-inclusive option. Consumer psychology favors lower advertised base rates even when total costs exceed competitors, enabling itemized pricing programs marketing lower tuition despite higher actual costs. Smart consumers calculate total costs rather than fixating on advertised base tuition. According to pricing structure research, students attending all-inclusive programs graduate with 23% less debt on average than students at itemized-pricing institutions advertising lower base tuition, indicating that transparent comprehensive pricing benefits consumers while complex itemized structures advantage institutions through cost obscuring enabling higher total charges.

Questions to ask revealing true program costs

Protect yourself by requesting comprehensive cost information before enrollment. Ask: What is total tuition cost for complete degree program? What mandatory fees exist and what are annual totals? Are there per-course fees beyond base tuition? What do textbooks and course materials typically cost annually? Are materials included in tuition or separately purchased? What proctoring fees exist and how many exams per term? Are there technology requirements or required purchases? What graduation and diploma fees exist? What is average total cost for student completing in [your expected timeline]? Can you provide written estimate of all costs for degree completion? What financial aid is available and is it renewable all years? Are there hidden costs students discover after enrollment? These detailed questions reveal true costs and institutions’ transparency. Programs providing clear detailed answers demonstrate honest pricing, while evasive responses about costs signal likely hidden fees and price manipulation. Never enroll without written comprehensive cost estimate—verbal claims prove unenforceable when surprise fees emerge.

The textbook and course materials cost manipulation

Textbook and course materials create substantial hidden costs averaging $1,200-1,800 annually—$4,800-7,200 over four-year degree beyond tuition and fees. Institutions manipulate these costs through multiple mechanisms. Publisher partnerships with kickback arrangements incentivize faculty adopting expensive new editions despite minimal content changes from cheaper previous editions. Bundled materials requirements prevent students buying used books or renting—publisher bundles including online access codes force new purchases at $200-350 per course versus $40-80 used alternatives. Custom editions created specifically for institutions prevent resale value and outside purchasing. Required materials sold only through institutional bookstores eliminate price competition enabling markups versus Amazon or other retailers.

Some programs address textbook costs through inclusive access models incorporating materials into tuition at negotiated bulk rates lower than individual retail prices. Open educational resources (OER) provide free textbooks for some courses eliminating costs entirely. Libraries maintain course reserves providing textbook access without purchase requirements. However, many programs maximize materials revenue through forced expensive purchases. Students can reduce costs by renting textbooks when possible, buying used copies when course requirements don’t mandate new editions with access codes, seeking international editions containing identical content at lower prices, utilizing library resources, sharing books with classmates, and investigating whether previous edition textbooks suffice despite faculty preferring expensive new editions. According to textbook cost research from the U.S. Government Accountability Office report on college textbook costs, students employing cost-reduction strategies reduce textbook expenses 60-75% compared to purchasing all new editions through bookstores, saving $3,000-5,000 over bachelor’s degree completion, though some programs prevent cost reduction through mandatory bundled materials and access code requirements forcing expensive new purchases regardless of student preferences or budget constraints.

Red flags indicating textbook cost manipulation

Warning signs of textbook cost exploitation include requirements that all materials be purchased through institutional bookstore without outside options, mandatory publisher bundles including online access codes for every course preventing used book purchases, custom editions specific to institution eliminating general market availability and resale value, faculty requiring newest editions despite minimal content changes from previous editions available cheaply used, and inability to obtain course material lists until after enrollment preventing cost research during program comparison. Legitimate programs provide material lists openly during recruitment, permit students sourcing materials anywhere including used book retailers and rentals, utilize open educational resources when possible reducing student costs, and adopt inclusive access models incorporating materials at bulk discount rates rather than individual retail pricing. Textbook costs exceeding $2,000 annually warrant scrutiny—some expensive fields require costly materials justifying high costs, but others exploit captive student market charging unnecessary premiums through publisher partnerships benefiting institutions and publishers while burdening students with avoidable expenses that affordable ethical programs minimize through OER adoption and purchasing flexibility.

Technology fees and online premium pricing

Online learning fees charging $75-150 per course represent particular pricing cynicism—students paying premium fees for online delivery despite online programs having dramatically lower costs than residential instruction. No physical classrooms require heating, cooling, or maintenance. No campus facilities need construction, upkeep, or staffing. Learning management system costs spread across thousands of students generate minimal per-student expense. Yet institutions charge online premiums claiming “online delivery costs” justify additional fees, when reality shows online instruction costs fraction of residential delivery. The premium represents pure profit extraction exploiting students who need online flexibility, not cost recovery for actual expenses.

Technology fees prove similarly questionable for online students paying $200-600 annually supposedly funding campus computer labs, technology infrastructure, and IT support services that distant online learners never access. Residential students using campus facilities might reasonably pay technology fees, but charging online students identical fees for facilities they can’t use constitutes unjustified revenue extraction. Some institutions justify technology fees claiming they fund learning management platforms benefiting all students, but LMS costs represent tiny fraction of collected technology fees—Blackboard or Canvas licensing costs $5-15 per student annually, yet institutions charge $250-500 technology fees generating $235-485 profit per online student through fee mislabeling. According to online pricing research, institutions charging separate online learning fees and technology fees to online students generate 35-45% profit margins on these fees after covering actual technology and delivery costs, demonstrating that fees represent profit centers rather than cost recovery and that institutions exploit online student need for flexibility charging premiums unjustified by actual delivery costs.

| Cost category | Claimed justification | Actual institutional cost | Typical student charge | Institutional profit/markup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning management system | Platform licensing and maintenance | $8-15 per student annually | $250-500 (technology fee) | $235-485 markup (94-97% profit) |

| Online course delivery | Instructional technology and support | $15-35 per course (incremental) | $75-150 per course | $60-115 markup (80-77% profit) |

| Video streaming/hosting | Bandwidth and hosting costs | $2-6 per student annually | Included in technology fee | Already covered by technology fee markup |

| Remote proctoring | Third-party proctoring service | $8-20 per exam (paid to vendor) | $15-45 per exam | $7-25 markup (46-56% profit) |

| Student support systems | Advising, tutoring, tech support | $120-180 per student annually | $180-380 (student services fee) | $60-200 markup (33-53% profit) |

Financial aid packaging and loan manipulation

Financial aid packaging influences student costs through how institutions combine grants, scholarships, loans, and work-study. Ethical institutions maximize grant aid before including loans, presenting aid packages showing grants first and loans as optional. Predatory institutions bury grant information while prominently displaying total “financial aid” including loans, creating impression of generous support when most aid constitutes debt rather than free money. Package might show “$22,000 financial aid awarded” consisting of $4,000 grants and $18,000 loans—technically true but misleadingly presented as if institution provided $22,000 assistance when $18,000 requires repayment with interest.

Students must carefully analyze aid packages distinguishing between grants/scholarships (free money never repaid), federal loans (debt with protections and favorable rates), and private loans (debt with fewer protections and often higher rates). Calculate actual costs as tuition/fees minus only grants/scholarships, recognizing loans as financing rather than aid reducing costs. Beware automatic loan acceptance in aid packages—some institutions enroll students in maximum loan amounts unless students actively decline, exploiting default bias where students accept pre-selected options without evaluation. According to financial aid packaging research from Federal Student Aid office, students receiving aid packages clearly separating grants from loans borrow 18% less than students receiving confusing packages presenting loans as “aid,” while default rates prove 24% lower among students with transparent aid packaging, indicating that clear aid communication enables better borrowing decisions while confusing presentation encourages excessive debt advantaging institutional revenue while harming student financial outcomes.

Deceptive versus transparent financial aid packaging

Sarah received financial aid offers from two online programs. University A package: “Congratulations! You’ve been awarded $24,500 in financial aid! This generous package includes Presidential Scholarship $3,500, need-based institutional grant $2,000, Federal Pell Grant $6,495, Federal Direct Subsidized Loan $3,500, Federal Direct Unsubsidized Loan $2,000, and Federal Parent PLUS Loan $7,000.” Large text emphasized $24,500 total, creating impression of $24,500 assistance toward $28,000 total costs. However, only $12,995 represented actual aid (grants/scholarships), while $12,505 was loans requiring repayment with interest—actual student payment $15,005 annually not $3,500 implied by “$24,500 aid” presentation. University B package presented differently: “Your financial aid consists of: FREE MONEY YOU NEVER REPAY: Federal Pell Grant $6,495, Merit Scholarship $4,000, State Grant $2,200, TOTAL GRANT AID: $12,695. LOANS YOU MUST REPAY: Federal Direct Subsidized Loan $3,500, Federal Direct Unsubsidized Loan $2,000 (OPTIONAL – you may decline), TOTAL IF ACCEPTING ALL LOANS: $5,500. Your actual cost: Tuition $19,200 minus grant aid $12,695 = $6,505 you pay from savings/work/loans.” Both packages offered similar aid, but University A presentation confused loans as aid encouraging acceptance of all offered debt, while University B clearly separated free aid from optional debt enabling informed borrowing decisions. Sarah chose University B declining unsubsidized loan, borrowing only $3,500 versus $12,505 she would have borrowed at University A, saving $9,005 in unnecessary debt and ~$2,200 interest from deceptive packaging encouraging maximal borrowing.

Comparing true costs across institutional types

Different institutional types demonstrate distinct cost structures requiring comparison beyond advertised tuition. Public university online programs charge in-state tuition ($300-450 per credit, $36,000-54,000 total) with moderate fees, providing value for state residents but expensive for out-of-state students paying 200-300% premiums. Private nonprofit online programs advertise higher tuition ($450-650 per credit, $54,000-78,000 sticker price) but often provide substantial institutional aid reducing net prices to competitive levels with publics. For-profit online programs advertise moderate tuition ($280-420 per credit) but provide minimal financial aid beyond federal loans, and research shows poor outcomes relative to costs. Competency-based programs like WGU charge flat-rate terms enabling motivated students completing degrees at $15,000-22,500 total—dramatically less than credit-hour programs when completion acceleration is feasible.

Calculating net price after typical financial aid for your income level provides accurate comparison. Public in-state online programs often prove cheapest for state residents after aid. Some private nonprofits offer generous aid making net prices competitive despite high sticker prices, particularly for low-income students. For-profits typically provide worst value through combination of moderate-high costs and poor outcomes. Competency-based provides best value for students capable of accelerated completion. Community college online programs at $100-180 per credit ($6,000-10,800 associate degrees) offer exceptional affordability, though credits may not transfer optimally to all bachelor’s programs. According to institutional cost comparison research from National Center for Education Statistics institutional cost data, average bachelor’s degree costs after financial aid range from $32,400 at public universities to $48,600 at private nonprofits to $52,800 at for-profits, with competency-based programs averaging $18,200—demonstrating substantial cost variation by institutional type that prospective students should consider during program selection alongside quality and outcome factors.

Comparing colleges by advertised tuition resembles comparing cars by manufacturer’s suggested retail price without considering dealer negotiations, available discounts, financing terms, fuel efficiency, maintenance costs, or resale value—focusing on single number ignoring numerous factors determining actual total ownership cost. Smart car buyers compare out-the-door prices after negotiations, calculate total ownership costs including fuel and maintenance over expected ownership period, consider reliability affecting long-term expenses, and evaluate resale value determining eventual actual cost. Smart college consumers compare net prices after financial aid rather than sticker tuition, calculate total costs including all fees and materials over expected completion timeline, consider completion rates and program quality affecting time-to-degree and total cost accumulation, and evaluate graduate outcomes determining return on educational investment. The prominent number (sticker price or advertised tuition) matters less than comprehensive cost analysis incorporating all financial factors over full product ownership or degree completion. Marketing emphasizes favorable single numbers, but informed consumers demand complete cost information enabling accurate comparison and optimal financial decisions.

Regional accreditation and cost-quality relationships

Regional accreditation provides quality assurance but doesn’t directly predict costs—both expensive and affordable programs hold legitimate accreditation. However, accreditation type correlates somewhat with cost structures and transparency. Regionally accredited institutions generally demonstrate more transparent pricing and fewer predatory fee practices compared to nationally accredited programs, with diploma mills lacking legitimate accreditation being most expensive relative to value (infinite cost for worthless credentials). Within regionally accredited institutions, public universities typically offer lower costs than private nonprofits, which prove cheaper than for-profits on average despite substantial variation within categories.

Cost alone shouldn’t determine program selection—$15,000 degree providing poor education and no employment outcomes proves more expensive than $45,000 degree leading to $65,000 career. However, numerous affordable regionally accredited programs provide quality education and strong outcomes, eliminating necessity of expensive programs for most students. Evaluate cost-to-outcome ratios rather than cost or outcomes independently. Programs costing $20,000 producing $55,000 median salaries provide better return than $60,000 programs producing $58,000 salaries—lower absolute earnings but far superior financial returns. According to cost-quality research, regional accreditation predicts completion rates and graduate outcomes more strongly than costs predict outcomes, indicating that accreditation verification should precede price comparison, but once legitimate accreditation is confirmed, affordable programs provide equivalent value to expensive alternatives for vast majority of students and career paths.

The myth of “you get what you pay for” in higher education

Consumer goods often demonstrate positive cost-quality correlation—expensive cars generally outperform cheap alternatives, luxury goods provide superior quality justifying premiums. However, higher education shows weak cost-quality correlation with numerous examples of expensive programs providing poor outcomes and affordable programs delivering excellent results. Western Governors University at $7,500 annually produces graduate outcomes matching or exceeding programs costing 3-5 times more. State university online programs at $36,000-45,000 total often achieve employment outcomes superior to $75,000-95,000 private alternatives. Conversely, expensive for-profit programs charging $55,000-75,000 frequently produce worse outcomes than affordable community college programs costing $8,000-12,000. This weak cost-quality correlation stems from education being experience good where quality proves difficult assessing before purchase, information asymmetries between institutions and consumers, and marketing sophistication creating price-quality perception associations not reflecting reality. Expensive programs sometimes provide superior outcomes through better resources, smaller classes, more support services, and stronger alumni networks, but often high costs reflect inefficient operations, excessive administrative spending, or profit maximization rather than educational quality. Always evaluate actual outcomes and total costs independently rather than assuming high prices signal quality—they frequently don’t in higher education markets.

Cost inflation trends and future projection

College costs increased 169% over past three decades while median incomes grew only 19%, creating affordability crisis affecting traditional and online programs. Online education initially promised cost reduction through eliminated physical infrastructure, but many programs match or exceed traditional tuition exploiting online flexibility premiums despite lower delivery costs. Average online bachelor’s degree costs increased 47% from 2010-2024 versus 38% for traditional programs, indicating online hasn’t delivered expected cost reductions. Some programs buck trends—competency-based online programs maintained relatively stable costs, community college online options remained affordable, and state university online expansions sometimes provided in-state pricing preventing inflation.

Future cost trends likely continue upward for most programs absent regulatory pressure or competitive market forces demanding affordability. However, competency-based expansion, increased state university online offerings, community college online growth, and employer-sponsored education benefits may create affordable alternatives preventing universal cost escalation. Students should account for inflation when planning multi-year programs—degree costs in year four may exceed year one by 8-12% requiring budget contingency. Accelerated completion protects against inflation by reducing exposure to cost increases. According to inflation analysis from National Center for Education Statistics, students completing degrees faster than peers save average 15-20% on total costs through reduced inflation exposure beyond direct timeline savings, making acceleration valuable even without per-term cost differences through inflation mitigation alone, and suggesting that degree completion speed provides financial protection against ongoing education cost inflation exceeding general economic inflation rates.

| Online program type | 2010 average cost | 2024 average cost | Percentage increase | Average annual inflation rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For-profit bachelor’s | $42,000 | $63,800 | 52% increase | 3.0% annually |

| Private nonprofit bachelor’s | $48,000 | $72,600 | 51% increase | 3.0% annually |

| Public out-of-state bachelor’s | $52,000 | $75,400 | 45% increase | 2.7% annually |

| Public in-state bachelor’s | $28,000 | $40,200 | 44% increase | 2.6% annually |

| Competency-based bachelor’s | $14,000 | $18,500 | 32% increase | 2.0% annually |

| Community college associate | $6,500 | $8,800 | 35% increase | 2.2% annually |

Frequently asked questions

Request written comprehensive cost estimates explicitly asking for tuition, all mandatory fees itemized, typical textbook and materials costs, technology requirements and associated costs, proctoring or testing fees, graduation and transcript fees, and estimated total for degree completion in your expected timeline. State you need complete information for financial planning and won’t enroll without transparent cost disclosure. Use net price calculators on institutional websites for personalized estimates based on income and family size. Compare estimates against IPEDS data showing average costs paid by similar students. Contact current students through Reddit or program-specific forums asking about surprise costs discovered after enrollment. If institutions refuse providing detailed cost information or seem evasive, interpret this as red flag indicating probable hidden fees and consider alternative programs offering transparent pricing. Legitimate programs welcome cost inquiries and provide detailed written estimates, while predatory programs resist transparency knowing complete cost disclosure would disadvantage them competitively.

Most online learning fees and technology fees charged to online students represent profit extraction rather than genuine cost recovery. Online delivery costs substantially less than residential instruction—no physical classrooms, campus facilities, or infrastructure requiring maintenance. Learning management systems cost $8-15 per student annually, yet technology fees charge $250-600. Online course delivery incremental costs run $15-35 per course, yet online learning fees charge $75-150. The fees generate 75-95% profit margins after covering actual costs. Some technology fees fund support services like advising and tutoring benefiting all students, but most revenue exceeds service costs considerably. Ethical institutions either eliminate these fees recognizing lower online costs, or charge less for online than residential programs reflecting actual cost differences. Programs charging online premiums exploit student need for flexibility rather than recovering legitimate costs. Reject programs with egregious online fees ($100+ per course online learning fees, $400+ annual technology fees) in favor of transparent programs with minimal fees or all-inclusive pricing incorporating reasonable costs without exploitative markups.

Multiple strategies reduce textbook expenses even with specific requirements: Compare prices across Amazon, Chegg, eCampus, and other textbook retailers rather than buying exclusively from bookstore. Rent textbooks when possible saving 40-60% versus purchasing new. Buy used copies if courses don’t require online access codes that come only with new books. Consider international editions containing identical content at fraction of U.S. prices. Check if previous editions suffice—many faculty assign newest editions but previous versions contain 95%+ identical content at 70-90% lower prices. Access course reserves at libraries providing textbook access without purchase. Share books with classmates alternating use or study together. Wait until classes start before buying—some “required” materials prove rarely used. Ask instructors if older editions or alternative books suffice. For expensive books you’ll reference frequently, buy used then resell after completion recovering 40-60% of cost. Use open educational resources (OER) free textbooks when available. Students employing these strategies typically reduce textbook costs 60-75% from full bookstore retail, saving $3,000-5,000 over bachelor’s completion versus purchasing all new editions.

Compare net prices after guaranteed aid rather than sticker prices or potential aid. Calculate: Tuition plus fees minus only grants and scholarships guaranteed in writing for all program years. Don’t count loans as aid—loans are financing requiring repayment. Verify whether aid continues all years or decreases after freshman year. Get multi-year aid commitments in writing rather than assuming continuation. Program advertising $18,000 tuition but providing $10,000 annual guaranteed grants costs actual $8,000 annually ($32,000 total). Program advertising $12,000 tuition with $3,000 aid costs actual $9,000 annually ($36,000 total)—higher-sticker program proves cheaper by $4,000 total. However, financial aid often varies by family circumstances—low-income students may receive more at expensive private schools through institutional aid, while middle-income students often find in-state public programs cheaper since high-tuition privates reserve best aid for very low income students. Run net price calculators for actual comparison with your specific financial situation rather than comparing advertised tuition or average net prices potentially differing from your circumstances substantially.

Create standardized comparison spreadsheet: For each program, list (1) tuition per credit or term multiplied by total credits/terms required, (2) all annual fees multiplied by expected years to completion, (3) estimated textbook and materials costs per year multiplied by years, (4) technology requirements and costs, (5) proctoring and testing fees, (6) graduation and misc fees, (7) subtotal of all direct costs. Then calculate (8) expected financial aid (grants/scholarships only, not loans) multiplied by years, (9) net cost (subtract aid from subtotal), (10) expected completion timeline, (11) opportunity cost from delayed career advancement if program takes longer than alternatives, (12) true total cost incorporating opportunity costs. Compare true total costs across programs rather than advertised tuition. Verify assumptions through net price calculators, current student inquiries, and institutional financial aid estimates. Weight costs against outcome data from College Scorecard—program costing $5,000 more but producing $8,000 higher average earnings provides better value. This comprehensive comparison takes 2-3 hours but prevents financial decisions based on incomplete information, typically saving $8,000-18,000 through optimal program selection versus choosing based on advertised tuition creating false affordability impressions.

Some cost variation reflects legitimate factors while much represents inefficiency or profit maximization. Legitimate reasons for higher costs include: small class sizes providing individualized attention (though many expensive programs use large classes contradicting claimed personalization), expensive equipment or software for specialized fields (engineering, design, healthcare), extensive clinical or internship placements requiring coordination, elite faculty with strong credentials demanding higher compensation, comprehensive support services genuinely improving outcomes, and prestigious alumni networks providing career advantages justifying premium. However, cost differences often stem from less legitimate factors: inefficient administration with excessive overhead, expensive physical campus infrastructure online programs don’t utilize but cross-subsidize, profit maximization at for-profit institutions, brand premium charging for reputation rather than educational quality, or poor management creating unnecessary expenses passed to students. Evaluate whether claimed justifications for higher costs translate to better outcomes—if expensive program produces equivalent graduate employment and earnings to affordable alternatives, premium probably doesn’t reflect genuine quality advantages but rather inefficiency or profit extraction. Most online programs show weak cost-quality correlation suggesting majority of cost variation stems from operational choices rather than educational necessity.

Conclusion: Empowered cost analysis prevents financial surprise

Online degree marketing creates affordability illusions through prominent low tuition figures while obscuring substantial additional costs through fees, materials, and program structure choices affecting total expenditure. Students making enrollment decisions based on advertised tuition without comprehensive cost analysis discover actual expenses exceeding expectations by 20-60%, creating budget crises forcing additional borrowing, program withdrawal after sunk costs make completion abandonment financially painful, or financial hardship affecting housing and basic needs. This systematic cost obscuring serves institutional revenue interests while harming student financial outcomes, yet protection proves straightforward through informed consumer behavior demanding transparent comprehensive cost disclosure before enrollment commitment.

Calculating total cost of ownership—tuition plus all fees, materials, technology, and opportunity costs from program duration—reveals genuine program costs enabling accurate comparison. Programs advertising low per-credit tuition often prove expensive through fee accumulation and extended completion timelines, while competency-based programs with higher per-term costs enable accelerated completion reducing total expenditure dramatically. Net price after guaranteed financial aid provides more accurate cost indicator than sticker tuition, though aid comparison requires verifying multi-year commitments rather than assuming freshman aid continues unchanged. All-inclusive transparent pricing benefits consumers despite sometimes higher advertised rates compared to deceptively itemized pricing hiding costs creating higher total expenditure than transparent alternatives.

The affordable transparent online programs exist—state universities providing in-state tuition, competency-based institutions enabling acceleration, community colleges offering associate degrees, and some private nonprofits with generous financial aid all prove genuinely affordable when total costs are calculated honestly. The challenge lies in distinguishing these legitimate affordable options from expensive programs disguising high costs through marketing emphasizing misleading low base prices while hiding substantial additional charges. Informed consumers demanding written comprehensive cost estimates, calculating total costs including all fees and materials over complete degree timeline, verifying claims through third-party data sources, and walking away from programs resisting cost transparency consistently choose programs costing $12,000-25,000 less over degree completion compared to students relying on advertised tuition for enrollment decisions. The 2-3 hours invested in comprehensive cost analysis generates returns of $4,000-8,000 per hour through superior program selection—exceptional return on time investment protecting educational budgets and preventing debt accumulation from hidden costs discovered too late for enrollment reversal without substantial financial loss.

Final takeaway

Calculate true program costs by combining tuition (per credit or per term × total required), mandatory annual fees (technology $200-600, student services $150-400, online learning $900-1,800), textbooks and materials ($1,200-1,800 annually), proctoring fees ($150-450 annually), technology requirements ($0-1,500 one-time), and graduation fees ($100-300), multiplying by expected years to completion—revealing actual costs exceeding advertised tuition by 25-55% at programs using deceptive fee structures. Compare total cost of ownership: Program advertising $380 per credit ($45,600 for 120 credits) with $4,200 annual fees over four years totals $62,400, while competency-based program charging $7,500 per six-month term completed in 2.5 years totals $18,750—70% less despite per-term price appearing higher. Request written estimates specifying all costs before enrollment, use net price calculators with accurate financial information determining aid-adjusted costs, verify multi-year aid commitments rather than assuming first-year packages continue unchanged, compare across 4+ programs calculating comprehensive costs for each, and reject programs resisting cost transparency through vague responses about fees or inability to provide total cost estimates. Legitimate affordable programs exist charging $15,000-45,000 total for bachelor’s completion through combination of reasonable base tuition, minimal exploitative fees, included materials, and completion timeline efficiency—protection requires identifying these honest programs through comprehensive cost analysis rather than accepting advertised tuition creating false affordability impressions while hidden fees generate 30-60% cost increases students discover after enrollment commitment when financial backing out proves impossible without losing substantial invested amounts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.